Democracy Shouldn't Require Heroic Effort

P0.3: Why Good Systems Don't Require Exceptional Humans

A guide from Protect Democracy lists 29 concrete actions citizens can take to protect democracy. It’s thoughtful work—comprehensive, actionable, carefully researched. The kind of resource civic organizations dream of creating.

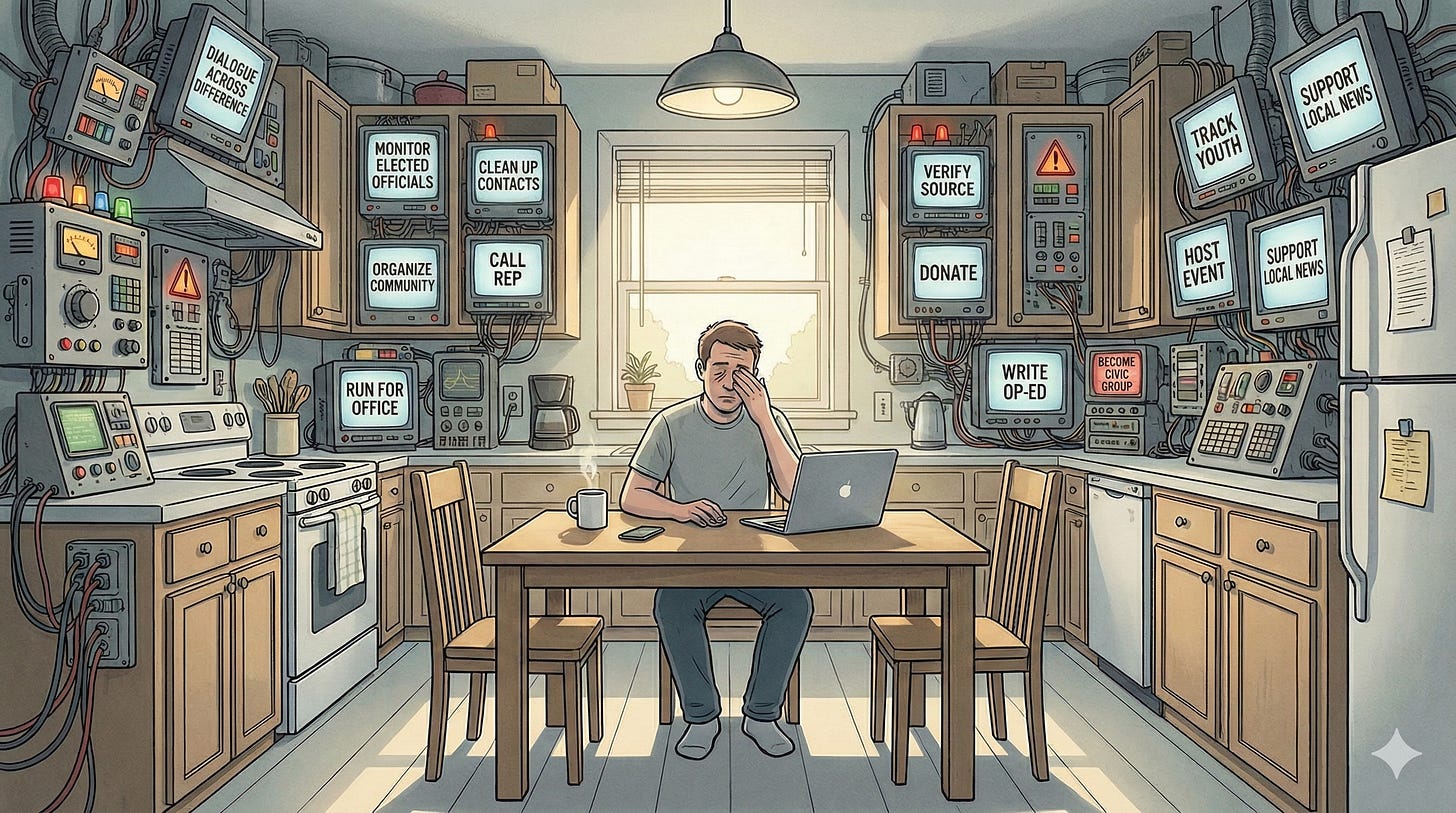

But reading through those 29 actions reveals something troubling: Why does our democracy require this much constant individual effort just to keep functioning? Clean up your contacts. Become an expert fact-checker. Organize community meetings. Dialogue across differences. Monitor elected officials. Volunteer. Donate. Run for office. It goes on.

Everyone agrees this feels exhausting, regardless of which side they’re on. Checking out of civic engagement isn’t a personal failing. It’s a rational response to a system that demands too much.

But here’s the thing: that exhaustion isn’t a failure of citizenship. It’s evidence of something else entirely.

What the Exhaustion Actually Reveals

As I explored in “The Bridge Can Be Fixed,” imagine a bridge where staying safe required every driver to personally inspect the structural integrity. Where you needed constant vigilance for failing supports. Where you had to organize with other drivers to patch problems as they appeared. Where you needed to dialogue with people who insisted the bridge was fine even as it swayed beneath you.

You wouldn’t say “drivers aren’t being vigilant enough.” You’d say “this bridge is structurally unsound.”

The need for heroic individual effort IS the evidence of structural failure.

If democracy is supposed to be government “for the people,” why does it demand a part-time second job from every citizen just to keep it functioning? That’s not government for the people—that’s government that depends on people to compensate for its design failures.

We can test any system with three diagnostic questions:

Does it scale? Can this work if most people don’t do it?

Does it handle normal humans? Or does it require everyone to be unusually informed, engaged, and charitable?

Is complexity solved once systemically? Or are individuals solving the same problems repeatedly?

Run the 29 actions through these questions. The answers are no, no, and “pushed out to millions of individuals to solve separately.” That’s not a citizenship problem. That’s a systems design problem.

And design problems are fixable.

The Pattern: “Just Let the Humans Handle It”

I used to work at a place where the solution to every coordination problem was the same: “just send me an email.” It felt simple. Low-tech. Personal. But it was actually a systems design failure disguised as simplicity.

Email doesn’t scale. It’s exclusive, opaque, and siloed—only recipients see it. Messages get buried, people go on vacation, context gets lost. There’s no way to track progress or ensure consistency. You end up with everyone solving the same problems individually, repeatedly, and poorly. The complexity hasn’t gone away—you’ve just kicked it down to humans who now have to compensate for bad design.

Those 29 civic actions follow the exact same pattern.

Take Action #4: “Become an expert at spotting mis- and disinformation.” The guide directs you to training resources from CISA and Poynter to learn how to identify false information. This is asking every citizen to personally become a fact-checking expert.

We don’t design other critical systems this way. You don’t personally verify that your medication is safe before taking it—we have the FDA for that. You don’t inspect restaurant kitchens yourself—we have health departments and structural regulations. When public safety is at stake, we build systemic safeguards because we can’t rely on every individual to develop expert-level skills.

But for political information? “Just let the humans handle it.”

Or consider Actions #9-17, which focus on building community: organize people, dialogue with opponents, attend meetings, connect with religious leaders, engage young people. These are literally professional skills. Community organizing is something people train for, get degrees in, build entire careers around. Yet the guide treats it as something every citizen should just... do. In their spare time. On top of their jobs and families and lives.

Actions #18-26 ask you to monitor elected officials, help candidates, become a poll worker, maybe run for office yourself. This is treating vigilance as the primary safeguard—expecting citizens to provide constant oversight because accountability isn’t built into the structure itself.

Each category follows the same formula: Instead of engineering systems that work, we ask individuals to compensate for the fact that they don’t.

Why This Approach Predictably Fails

The “just let humans handle it” approach has predictable failure modes. They’re the same ones that made email-driven processes fail at my old workplace.

It doesn’t scale. These actions only work if everyone does them consistently. But people have jobs, kids, lives. Look at who actually has time for sustained civic engagement: retirees, people with flexible schedules, those who don’t work multiple jobs. The system predictably excludes everyone else. This isn’t a bug—it’s the outcome you’d expect when you design something that requires constant individual heroics.

It exhausts people. Twenty-nine things! Democracy as a full-time job! When baseline function requires heroic effort, exhaustion is what you get. Your car doesn’t require you to manually monitor every sensor and system. Good engineering means the car handles routine monitoring itself and only alerts you when something needs attention. But our democracy? It demands constant vigilance for basic operation.

And when people get exhausted? They disengage. Or they find simpler narratives—a villain to blame instead of a system to understand. The exhaustion doesn’t just fail to protect democracy; it actively pushes people toward the shortcuts that make things worse.

It requires people to take the moral high ground. Action #13 tells you to “dialogue with people who don’t agree with you” and emphasizes that “your goal is NOT to convince them they’re wrong” but to understand their perspective. This asks citizens to be heroically charitable, patient, and empathetic across political divides.

Here’s the problem: we can’t build systems that rely on people taking the moral high ground. Good systems work even when humans are flawed, tired, busy, or just normal. Asking everyone to be unusually virtuous as a design requirement means you’ve given up on actual design.

It kicks complexity down to individuals. Instead of solving problems once at the system level, we’re asking millions of people to each solve the same problems individually. Fact-checking. Organizing. Monitoring. Engaging. It’s like giving every driver their own traffic engineering problem instead of just installing traffic lights. And most people solve these problems poorly because they’re not trained for it—because why would they be?

The Immune System We’re Missing

The Immune System Series examines how misinformation spreads through our political system via a five-stage cascade—from individual exposure to viral spread to system-wide adoption. We’ve engineered virality for political information but never built the immune system to go with it.

Action #4’s approach to misinformation is pure Stage 1 thinking: individual personal responsibility. It tells you to become a fact-checking expert. But this is like asking individual cells to fight viruses without an immune system—each cell defending itself rather than having a coordinated system-level response. By the time you’ve personally verified that something is false, it’s already spread everywhere. You’re not preventing infection—you’re just documenting it after the fact.

Real immune systems work differently. They operate at Stage 4: systemic, coordinated response. They have structural mechanisms that identify and neutralize threats before they can spread through the entire organism. The body doesn’t ask every cell to become an immunology expert. It has specialized systems that handle this at scale.

Our democracy has no equivalent. No systemic filters to catch mis- and disinformation before it spreads. No structural mechanisms to verify information provenance. No built-in incentives for accuracy over engagement. We have individuals trying to fight Stage 4 problems with Stage 1 solutions—and then we wonder why it’s not working.

The Design Principle We’re Missing

Good systems make the right thing easy and the wrong thing hard. They work even when humans are just being human.

We already know how to design complex systems for normal humans—we do it everywhere else. We just haven’t applied those same principles to the way we govern.

Consider how we handle food safety. You don’t personally inspect every restaurant kitchen. You don’t need to become an expert in foodborne pathogens. You don’t organize with other diners to monitor sanitation practices. We have the FDA, health inspectors, and structural regulations that make it hard for restaurants to serve unsafe food. The system does the heavy lifting.

Or traffic. You don’t personally negotiate every intersection. You don’t need everyone to be unusually courteous and skilled. We have lights, signs, and engineered flow patterns that make safe navigation straightforward even when drivers are distracted or in a hurry.

Or currency. You don’t verify that every bill isn’t counterfeit. We have designed security features and enforcement mechanisms that make counterfeiting hard and detection easy.

But democracy? We have no systemic information filters. No structural engagement mechanisms that work for normal people living normal lives. No automatic accountability systems. Instead, we fall back on the oldest non-solution: “just let the humans handle it.”

What Structural Solutions Could Look Like

This piece doesn’t prescribe specific solutions. Its job is to show that structural alternatives exist—that we’re not trapped in this design forever.

ILLUSTRATIVE EXAMPLE—Information Quality:

Consider what government information transparency might look like. Budget data you can actually read without a finance degree. Policy impact tracking that shows what legislation actually did, not just what it promised. Legislative text with clear explanations of what changes and why. Regulatory decisions with visible reasoning chains. We already require this kind of transparency from public companies—annual reports, earnings calls, plain-language risk disclosures. Government could work the same way: structural transparency that makes understanding the default rather than a research project. This is ONE possible approach among many, meant to illustrate building systemic clarity rather than asking every citizen to become a policy analyst.

ILLUSTRATIVE EXAMPLE—Engagement:

Think about what happened with 401(k) participation rates. When enrollment was opt-in and required active steps, participation was low. Switch to automatic enrollment with an opt-out option, and participation soared. The same principle could apply to democratic participation—design mechanisms that make engagement fit into normal life rather than requiring exceptional time commitment. Designed deliberation processes with clear structure and meaningful outcomes, rather than asking everyone to spontaneously “have a conversation.” This is a thought experiment about making participation accessible, not a specific policy proposal.

ILLUSTRATIVE EXAMPLE—Accountability:

Modern engineering systems have automatic failure detection and alerts. Your car’s computer monitors hundreds of systems and only notifies you when something needs attention. What if government had similar built-in feedback loops? Structural incentives that reward cooperation and make gridlock costly—not through punishment, but through automatic consequences that encourage resolution. Like how engineering systems create pressure to fix problems before they cascade into failures. ONE way to think about building accountability into the architecture rather than relying on constant citizen vigilance.

These examples span different approaches and philosophies. The point isn’t which specific solutions are best—it’s that we CAN engineer better systems. We just have to choose to.

The Real Work

Those 29 actions are necessary given the system we have. The people creating these guides are doing important work. They’re helping citizens navigate a system that badly needs navigation help.

But we can also ask: Why is our system designed this way?

Other democracies don’t require this level of heroic individual effort for basic function. They still struggle with their own challenges, but basic participation doesn’t require citizens to moonlight as full-time democracy mechanics. Other infrastructure doesn’t tell people to compensate for bad design through personal heroics. We know how to engineer systems that work for normal humans. We do it everywhere else.

Good systems don’t remove citizen agency—they free it up for the choices that actually matter. There’s a difference between maintaining the bridge (heroic effort just to keep it standing) and steering the car (deciding where we go together). Right now, we’re so busy patching structural failures that we barely have energy left for the real work of democracy: debating values, setting direction, holding genuine disagreements about where we should head.

The real work is doing both things at once. Under our current system, we need individual civic engagement—until the bridge is fixed, we have no choice but to be vigilant drivers. But we shouldn’t accept this as the permanent state of affairs. Currently we need fact-checking and community organizing and vigilant oversight—but we need structural mechanisms that make these things unnecessary for baseline operation.

Start asking: What would it look like if democracy worked for normal humans living normal lives? What would it look like if staying informed didn’t require becoming an expert? If participating didn’t require professional-level organizing skills? If accountability happened automatically rather than through constant citizen pressure?

That’s what good systems design does. It works even when humans are just... human. It makes the right thing easy instead of heroic.

Government for the people shouldn’t require superhuman people.

Our democracy can be that kind of system. But first, we have to stop accepting “just let the humans handle it” as an answer.

This piece examines structural versus individual approaches to democratic resilience, building on themes from “The Bridge Can Be Fixed“ and “The Immune System Series.” For more on structural reform, visit Statecraft Blueprint.

I like how you think. Our system was designed before Hitler, but after Kings. We believed the guardrails of the Constitution could hold. What our innocence got us over the past 8 decades was the rot happening from within went unnoticed or considered it fixable. The evil part of humanity, the flaw, wasn’t addressed because not all agreed it was a flaw.