The Bridge Can Be Fixed

P0.2: What the structural lens reveals that partisan framing misses

📌 This essay has been rewritten.

After publishing this piece, I realized I’d made the exact mistake I warn against in my writing: I spent 2,000 words explaining why the bridge was collapsing before getting to the part about how it can be fixed.

If you’re already exhausted by political dysfunction, you don’t need a detailed tour of the wreckage. You need to know there’s a way forward.

Read “The Bridge Can Be Fixed (Redux)” — same core insight, better emotional journey. Hope first.

The original remains below for anyone curious about the evolution.

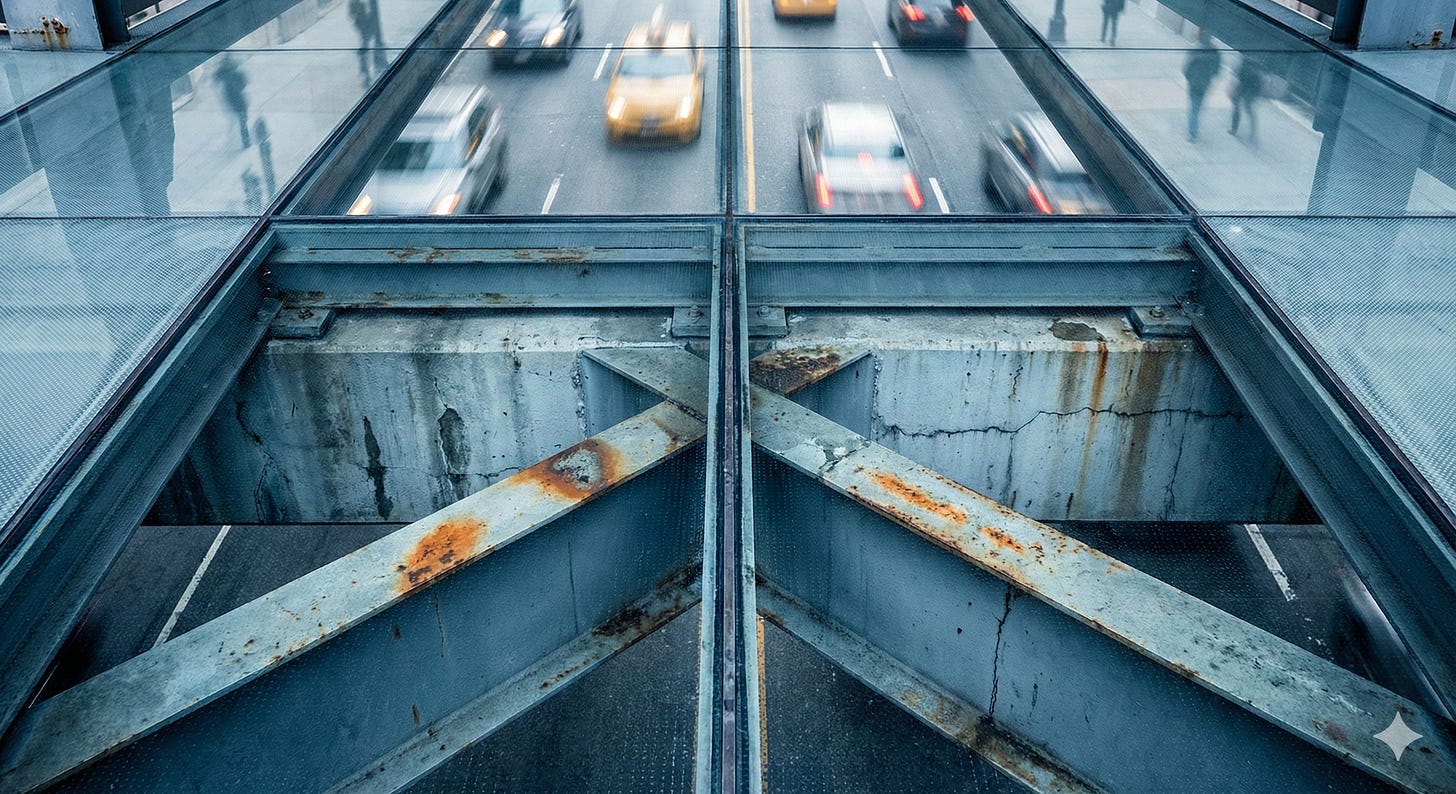

Imagine you’re a structural engineer inspecting a bridge. You notice rusted beams buckling under weight, stress fractures in the support columns, and foundations settling unevenly. The bridge was built in the 1800s for horse-and-buggy traffic. It now carries semi-trucks, buses, and thousands of commuters daily—loads it was never designed to handle.

Meanwhile, on the bridge deck above, two groups are having an increasingly heated argument about which lanes should get priority. One side wants the left lanes prioritized. The other wants the right lanes to move faster. Both are absolutely convinced they’re right—that if their preferred traffic pattern were implemented, everything would work better.

Neither group is looking down at the beams.

This is American governance in 2025.

Our work is simple: make people look down at the beams. Once you see the structural failures, you can’t unsee them. And once enough people see them, we can start building what comes next.

The Argument We’re Not Having

Pick any major policy debate: healthcare, immigration, climate change, national debt, education, infrastructure, AI regulation. You’ll find the same pattern:

Passionate arguments about what policies we should adopt

Bitter fights over which values should take priority

Endless finger-pointing about who’s blocking progress

Absolute silence about why the system can’t implement anything effectively regardless of who wins

Government shutdowns happen like clockwork. Neither party wants them—they’re universally acknowledged as dysfunctional—yet they keep happening. That’s not a policy disagreement. That’s a structural failure.

Congress can’t pass budgets on time. Both sides are frustrated by this. They blame each other for it. But the mechanism that produces this outcome operates regardless of which party controls what. That’s not about bad actors. That’s about bad architecture.

Policy lurches wildly every 4-8 years. Businesses can’t plan. Citizens can’t predict what rules they’ll be living under. International partners don’t know if agreements will hold. Everyone agrees this is problematic. Yet it continues. Why? Because the system is designed to produce exactly this outcome.

The Structural Lens

Here’s what partisan framing misses: the infrastructure itself is failing.

A structural lens doesn’t ask “what should government do?” It asks: “how does this mechanism work? What outcomes does it produce? Is it fit for purpose?”

This isn’t splitting the difference between left and right. It’s seeing what both perspectives miss entirely.

Consider what’s changed since the Constitution was written:

In 1787, governance involved:

13 states along the Eastern seaboard

4 million people (about the current population of Oklahoma)

Communication by horseback

An agricultural economy

No permanent federal bureaucracy

No political parties (they hoped)

Limited federal responsibilities

In 2025, governance involves:

50 states spanning a continent plus territories

340 million people across six time zones

Instantaneous global communication

A complex, interconnected global economy

Millions of federal employees

Entrenched two-party duopoly

Nuclear weapons, pandemic response, AI regulation, climate policy, cybersecurity, space commerce, genetic engineering, and countless other domains the Founders couldn’t have imagined

You don’t need to be a political scientist to see the problem. We’re running 21st-century loads on 18th-century infrastructure. The beams are buckling. Everyone can see it.

What Both Parties Miss

The left sees dysfunction and concludes: “If only we had power, we could fix this.”

The right sees dysfunction and concludes: “If only we had power, we could fix this.”

Both are wrong. The problem isn’t who has power. The problem is that the system itself has become incapable of processing complexity, implementing policy effectively, or responding to rapid change—regardless of who’s in charge.

This isn’t about bad people in government. Most people working in government are trying their best within an impossible system. You can see this at the individual level: dedicated public servants who are frustrated by the same gridlock and dysfunction that frustrates citizens.

The system itself produces bad outcomes because it’s structurally mismatched to the job it’s being asked to do.

The Bridge Is Failing

Here’s what structural failure looks like in practice:

Government shutdowns: Not because anyone wants them. They happen because the budget process itself is broken—it literally cannot complete its basic function on schedule anymore.

Policy whiplash: Not because politicians are uniquely fickle. It happens because power oscillates between parties with no mechanism for stability or continuity in long-term policy.

Inability to address long-term challenges: Not because no one cares about the future. It happens because the system structurally rewards short-term thinking and punishes anyone who tries to solve problems beyond the next election cycle.

Recurring crises: The same problems resurface every few years—immigration, debt ceiling, infrastructure, trade policy—not because previous solutions worked. Because the system can’t implement durable solutions at all.

Gridlock even with unified government: Not just a divided government problem. Even when one party controls everything, the system still struggles to function because the architecture itself creates veto points and perverse incentives at every turn.

The Collapse of Redundancy: Think about the “legislative funnel.” In the past, Congress used 12 separate appropriations subcommittees to pass 12 separate funding bills—like a bridge resting on 12 independent pillars. If one pillar had a problem, the bridge stood on the other eleven. Today, structural erosion has forced almost all spending into massive, singular “omnibus” packages. We have effectively replaced 12 pillars with one precarious column. Now, a disagreement over any single issue—border security, healthcare, or a specific regulation—threatens to collapse the entire structure (a government shutdown). That isn’t a failure of willpower; it’s a textbook engineering failure. We stripped the system of its structural redundancy.

These aren’t policy failures. They’re structural failures. You can see them directly, like rust on those bridge beams.

The Difference This Makes

When you adopt a structural lens, the conversation changes completely:

Partisan framing says: “We need to win more elections so we can implement our policies.”

Structural framing says: “We need systems that can actually implement policy effectively, regardless of which vision wins.”

Partisan framing says: “The other side is blocking progress.”

Structural framing says: “The architecture makes progress nearly impossible for either side.”

Partisan framing says: “If we just had better leaders...”

Structural framing says: “The system turns good leaders into frustrated participants in dysfunction.”

Partisan framing says: “This is about values—what should we do?”

Structural framing says: “This is about capacity—can the system do anything effectively?”

This isn’t about being above the fray or pretending both sides are the same. It’s about recognizing that both sides are constrained by infrastructure that’s failing under modern loads.

Making the Invisible Visible

The hardest part isn’t fixing the bridge. It’s getting people to look down at the beams.

We’ve spent so long arguing about traffic patterns—which policies should get priority, whose values should win—that we’ve stopped noticing the infrastructure itself. The dysfunction has become background noise. We’re so used to government shutdowns, gridlock, and policy whiplash that we think this is just how government works.

It isn’t.

Other democracies don’t experience government shutdowns. Many have found ways to provide policy continuity across administrations. Systems exist that can process complexity and respond to change. We know this is possible because we can see it working elsewhere.

The question isn’t whether better systems are theoretically possible. The question is whether we can see that our current system is failing—and whether we’re willing to do something about it.

What Comes Next

This is not a policy platform. We’re not advocating for specific reforms (yet). We’re doing something more fundamental: making visible what partisan framing renders invisible.

Once you see it—once you notice that the infrastructure itself is failing—you can’t unsee it. Every government shutdown becomes evidence. Every policy whiplash becomes a data point. Every recurring crisis becomes a symptom of structural failure.

And once you see it, you can start asking different questions:

What would infrastructure fit for 21st-century governance actually look like?

How do we build systems that can process complexity rather than collapse under it?

What changes would allow durable policy implementation instead of endless whiplash?

How do we create structures that reward long-term thinking instead of punishing it?

These aren’t partisan questions. They’re engineering questions. And they’re questions we desperately need to start asking.

The Bridge Can Be Fixed

Here’s the hope: structural problems have structural solutions.

This isn’t about changing human nature or waiting for perfect leaders. It’s about building systems that work with human nature as it is—systems that channel self-interest toward collective good, that make good governance the path of least resistance, that reward solving problems instead of creating them.

We built the original bridge in the 1700s. It was a marvel of its time, revolutionary in its design. It served us well for generations.

But now the loads have changed. The beams are buckling. And pretending we can solve this by arguing about traffic patterns—or by blaming the other drivers—is delusional.

We need to look down at the beams. We need to acknowledge that the infrastructure itself is failing. And then we need to start building what comes next.

Not because we agree on everything. But because we all depend on the same bridge.

This is what the structural lens reveals that partisan framing misses. Both parties are debating which policies to implement while missing that the system itself has become incapable of implementing anything effectively. If you’ve never looked at American governance this way before, you’re not alone. Most of us haven’t. That’s what we’re here to change.

You are so deeply incisive. Wow.