The Unavoidable Need for Nuance

P2.1.1 When Politics Demands Higher Order Thinking

Section I: Introduction: The Crisis of Complexity

The great crisis of modern governance is not a lack of political will; it is an institutional aversion to complexity. As we enter Day 36 of the longest government shutdown in American history, millions of Americans confront the predictable consequences of this aversion: 42 million SNAP recipients receiving only half their food assistance, 58,600 children losing access to Head Start programs, airports experiencing cascading delays from air traffic controller shortages, and millions more facing the loss of healthcare subsidies by year’s end.

Yet the political debate remains stubbornly, destructively simple: Whose fault is it?

This question reveals the structural problem. A funding crisis affecting tens of millions of Americans, driven by the complex intersection of healthcare policy, budget reconciliation procedures, and competing legislative priorities, cannot be reduced to a blame game. But the political system is currently designed as an anti-intellectual machine—one that actively punishes the nuance required to solve 21st-century problems. The political success of a leader is measured in the snappy soundbite and the black-and-white position. This is the structural incentive at work: The campaign trail demands declarations like, “Solving this problem is so easy!” while the reality of office forces an embarrassed whisper: “Who knew healthcare was so complicated?”

The phrase “it’s complicated” is treated as an admission of weakness or indecision. Watch any shutdown press conference: politicians on both sides offer maximum certainty about minimum complexity. “Democrats refuse to negotiate.” “Republicans are holding Americans hostage.” Both statements may be politically useful. Neither captures the actual policy challenge: how to structure healthcare subsidies, balance competing budget priorities, and fund government operations when the legislative calendar collides with fiscal deadlines and expiring statutory authorities.

This institutional aversion to deep analysis is the most critical design flaw of modern governance. It starves the system of the intellectual rigor required to maintain a functioning 21st-century state. The result is not just rhetorical—it’s material. Food banks report lines stretching for hours. Federal employees volunteer at emergency pantries to serve their colleagues. Airports consider closing airspace sections. This is what happens when governing systems optimize for communicability over functionality: policy gridlock doesn’t remain abstract—it becomes 42 million people opening their mailboxes to find half the food assistance they need to feed their families.

Section II: The Failure of Analogous Reasoning in Politics

The source of this intellectual failure is a reliance on Reasoning by Analogy. This is the political default: to encounter a new problem and immediately search for a historical parallel—a legislative “pattern match”—rather than treating the problem as a unique system demanding a unique design. The goal is to apply an old, politically palatable solution rather than seek a novel, complex, and effective one.

This failure is never more stark than in economic crisis management. Consider the intellectual whiplash between the 2008 Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 Economic Crisis.

The 2008 Financial Crisis was a classic demand-side recession, where trust evaporated and spending ceased. The correct, if delayed, remedy involved liquidity injections and measures to stimulate consumption. Banks were frozen, credit markets seized, and the economy needed jump-starting through restored confidence and available capital.

Yet, when the supply-side crisis of COVID-19 hit—a crisis defined not by a lack of money, but by an absolute lack of goods and labor—Congress reached for the 2008 analog: massive, untargeted stimulus.[1] This act of intellectual laziness poured financial gasoline onto a supply-constrained fire, creating the inflationary environment that persists today.[2]

What actually happened:

Businesses couldn’t produce goods (supply chains broken, factories closed)

Workers couldn’t work (lockdowns, illness, childcare collapse)

Supply of goods and services: drastically reduced

Demand stimulus: massively increased

Result: Money chasing fewer goods = inflation

RV prices surged dramatically.[3] Housing exploded.[4] Everything cost more. This wasn’t some mysterious economic phenomenon—it was the predictable result of applying a demand-side solution to a supply-side problem.

What was actually needed: Instead of a nuanced, systemic response that secured housing and employment via limited guarantees (keeping people housed and employed while we fixed the supply problems), the analogous solution was applied indiscriminately, driving up the price of everything from consumer goods to RVs.

This is the intellectual cost of simplicity: the political success of a simple narrative (giving everyone money) overrides the economic reality that demanded a higher-order, nuanced policy. We must reject the political notion that complexity equals inefficiency. The opposite is true: sophisticated problems demand sophisticated, optimized solutions.

The current government shutdown demonstrates the same intellectual failure, though the mechanism differs. Both parties are reasoning by analogy to previous shutdowns—particularly the 35-day 2019 shutdown over border wall funding. The pattern feels familiar: divided government, high-stakes policy disagreement, each side waiting for public pressure to force the other to capitulate.

But the analogy fails. The 2019 shutdown centered on a single, discrete policy question: funding for a border wall. The resolution, while politically difficult, was structurally simple—either appropriate the funds or don’t. The 2025 shutdown involves the expiration of enhanced Affordable Care Act premium subsidies, affecting healthcare access for millions, combined with routine government funding, SNAP contingency fund depletion, and cascading operational failures across multiple agencies. This is not a single-issue standoff that ends when one side blinks. It’s a multi-dimensional policy crisis requiring sophisticated solutions about insurance market structure, budget reconciliation rules, appropriations procedures, and emergency funding authorities.

Yet the political debate compresses to the 2019 template: “Who will blink first?” The precedent trap leads both parties to treat this as a zero-sum hostage negotiation rather than a complex system failure demanding coordinated intervention. The analogous reasoning predicts a clean resolution through raw political will. The actual situation—with SNAP benefits halved, Head Start grants frozen, and airport operations degraded—reveals a system that cannot be solved by political theater. You cannot negotiate your way out of depleted contingency funds. You cannot blame your way to functional food assistance. The complexity is unavoidable. The only question is whether our governing institutions can engage with it before the cascading failures become catastrophic.

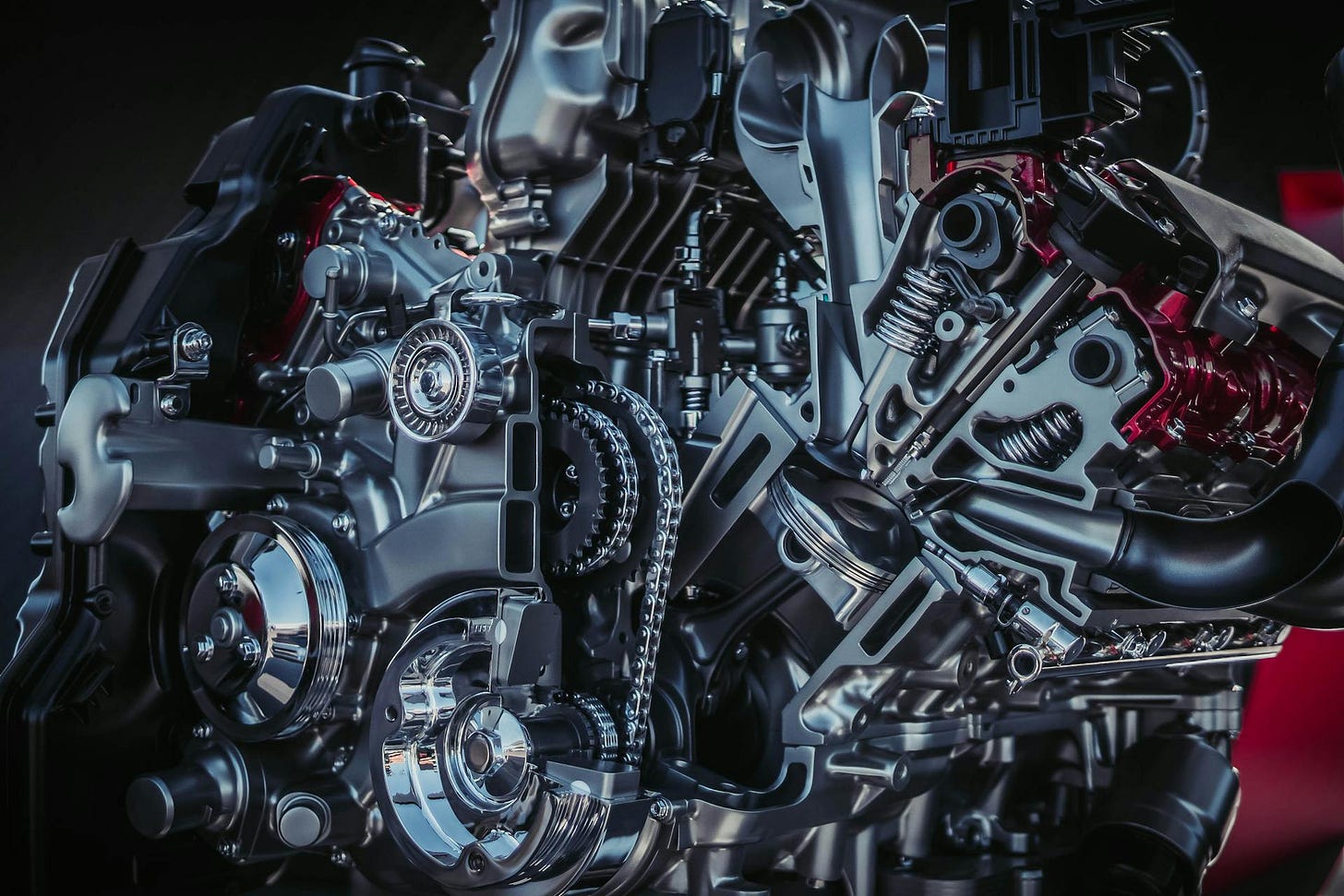

Over time, all high-performing systems—from biology to engineering—evolve toward greater sophistication to extract greater efficiency. A modern internal combustion engine is a marvel of sophistication—it is designed with dozens of sensors and control units not to be confusing, but to be supremely efficient and high-performing. The same principle applies to governance. The pursuit of political simplicity is an act of intellectual regression.

Section III: The Structural Incentives That Punish Nuance

The anti-intellectual design of modern politics isn’t accidental—it’s the predictable output of three reinforcing structural incentives. Each individually discourages nuanced thinking; together, they create a system where sophisticated analysis is not just unrewarded but actively dangerous to political survival.

A. The Soundbite Imperative

Political success is measured in seconds, not substance. A candidate has roughly 8-10 seconds to communicate a position before a voter’s attention shifts or a news editor cuts to the next segment.[5] This isn’t a recent phenomenon created by social media—it’s been the fundamental constraint of broadcast politics since the 1960s—but it has intensified with fragmented attention and algorithmic amplification.

The result is what we might call the complexity penalty: any position that requires more than a single sentence to explain is, by definition, too complex to communicate effectively in modern political discourse. “Build the wall” fits in a soundbite. “Comprehensive immigration reform that addresses visa overstays, asylum processing, temporary worker programs, border security technology, and regional economic development” does not.

This creates a perverse optimization: politicians don’t optimize for policy effectiveness; they optimize for communicability. The question isn’t “Will this solve the problem?” but rather “Can I explain this in ten seconds?” If the answer is no, the policy is politically dead regardless of its merit.

Healthcare provides the clearest example of this dynamic. The policy space includes dozens of critical variables: insurance market structure, provider payment models, pharmaceutical pricing mechanisms, medical device regulation, malpractice liability frameworks, graduate medical education funding, certificate-of-need laws, scope-of-practice regulations, health information technology standards, and more. Each variable involves trade-offs between cost, quality, access, and innovation.

But the political debate compresses to two positions: “Medicare for All” versus “Free Market Healthcare.” Both are radical oversimplifications. Medicare for All elides questions of implementation timeline, provider payment rates, coverage scope, cost controls, and the transition for 180 million people with employer-sponsored insurance.[6] Free Market Healthcare ignores information asymmetries, adverse selection, emergency care obligations, the impossibility of true consumer choice in acute care, and the reality that healthcare markets fail basic economic assumptions about rational actors and perfect information.

Neither soundbite represents a workable policy—they represent the limits of what can be communicated in the format that politics demands. The actual policy work happens in thousands of pages of legislative text that almost no one reads, drafted by staffers working from lobby-provided research, implementing compromises that satisfy no one because the public debate occurred at a level of simplification that made coherent policy impossible.

The information diet determines decision quality. We have optimized our political information system for speed and emotional resonance, not for accuracy or comprehension. The politician who says, “This is complicated, and here are the trade-offs we need to consider” loses to the one who says, “I have a simple solution.” Every time.

The current shutdown provides a real-time demonstration of this dynamic. The actual policy challenge is genuinely complex: enhanced ACA premium subsidies expire at year’s end, threatening to increase healthcare costs for millions; the federal government requires funding; SNAP contingency funds are depleted; appropriations bills are incomplete; and budget reconciliation procedures create procedural constraints. Each element involves technical details, legal authorities, implementation timelines, and practical consequences that require careful analysis.

But the communicable versions? “Democrats won’t fund the government unless Republicans give them everything they want.” Or: “Republicans are forcing a shutdown to deny Americans healthcare.” Both compress dozens of policy variables into a ten-second attack line. Neither explains how enhanced premium subsidies work, why contingency funds exist, what appropriations procedures require, or how the pieces interconnect. A politician who tried to explain the actual situation—”We need to address the interaction between ACA subsidy expiration, appropriations deadlines, SNAP contingency fund status, and budget reconciliation constraints”—would lose the news cycle to whoever delivered the better soundbite.

The result is visible in the shutdown’s consequences. SNAP recipients don’t need to know which party is at fault—they need their food assistance. Air travelers don’t care about parliamentary procedure—they need air traffic controllers. Federal employees don’t want talking points—they need paychecks. The system optimizes for blame assignment over problem-solving because blame fits in a soundbite and solutions require paragraphs. When the architecture rewards simplicity over substance, Americans get maximum rhetoric and minimum relief.

B. The Expertise Paradox

Voters face an impossible cognitive task: evaluate candidates’ competence on issues where the voters themselves lack expertise. Most Americans are not macroeconomists, epidemiologists, or foreign policy strategists. Yet they must choose leaders who will make decisions in all these domains.

Faced with this impossible evaluation, voters use a heuristic: confidence. The candidate who projects certainty appears competent, while the candidate who expresses uncertainty appears weak or uninformed. This creates what we call the expertise paradox: the more a candidate actually knows about a complex subject, the more likely they are to express appropriate uncertainty about predictions and acknowledge trade-offs—and the less competent they appear to voters who lack the knowledge to distinguish between false certainty and genuine expertise.

“I don’t know” should be an acceptable—even admirable—answer when followed by “but here’s how I would find out” or “here’s what the evidence shows.” In reality, it’s political suicide. Candidates learn quickly never to admit uncertainty, never to acknowledge complexity, and never to say that reasonable people might disagree.

The result is what we might call pretend epistemology: politicians claiming knowledge they don’t have and certainty that doesn’t exist. They must act as if every problem has a clear solution, every policy has predictable outcomes, and every expert agrees—when none of these things are true.

Consider immigration policy. The actual policy space involves approximately 20-30 distinct policy dimensions: border security technology and personnel, visa processing systems, asylum claim adjudication, temporary worker programs, enforcement priorities, deportation procedures, detention standards, legal immigration quotas by category, refugee resettlement, international cooperation with origin countries, economic development in source regions, employer verification systems, path-to-citizenship criteria, family reunification rules, and more.

Each dimension involves empirical questions (What actually works?), value trade-offs (Who wins and loses?), and implementation challenges (Can we actually do this?). Experts disagree—not because they’re incompetent, but because the evidence is mixed, the values are contested, and the predictions are uncertain.

But the political debate compresses to two positions: “Build the wall” versus “Open borders.” Both are caricatures. Neither party actually advocates for completely open borders, and no serious immigration expert thinks a physical wall addresses the majority of immigration policy challenges (visa overstays account for roughly 40% of undocumented immigration and aren’t stopped by walls).[7]

The politician who says, “Immigration is multifaceted, involving security, economic, humanitarian, and diplomatic considerations that require balanced trade-offs” is telling the truth. But they lose the election to the one who says, “Secure the border” or “No human is illegal.” The system rewards the simple lie over the complex truth.

C. The Precedent Trap

Human beings are pattern-matching machines. When we encounter a new problem, we instinctively search our memory for something similar we’ve seen before. This served us well in evolutionary history—if that rustling in the bushes was a predator last time, treat it as a predator this time.

But this cognitive pattern, when applied to policy, produces the precedent trap: every new problem gets mapped onto an old problem, and the old solution gets applied regardless of whether the problems are actually analogous. Political leaders aren’t stupid for doing this—they’re responding to a structural incentive. Citing precedent provides political cover. “We did this before” sounds reasonable. “We need to try something completely novel” sounds risky.

The pattern is consistent across crises:

September 11, 2001: Terrorist attacks on American soil. The precedent: Pearl Harbor (attack by foreign enemy). The analogous response: Declare war, invade the enemy’s territory. The problem: Al-Qaeda wasn’t a nation-state with territory to invade. The Iraq War was justified partially through this false analogy—treating a terrorist network as if it were Imperial Japan.[8]

2008 Financial Crisis: Credit markets freeze, economy contracts. The precedent: The Great Depression. The analogous response: Massive liquidity injection, stimulus spending, banking reform. The result: Eventually effective, though the analogy wasn’t perfect (Depression was partly caused by monetary contraction; 2008 was caused by financial system complexity and systemic risk).

2020 COVID-19: Economic collapse from pandemic. The precedent: 2008 (economy in crisis). The analogous response: Massive stimulus. The problem: 2008 was demand-side (people stopped spending); COVID was supply-side (people couldn’t produce). Applying a demand-side solution to a supply-side problem created inflation. The correct analogy might have been wartime production challenges or natural disaster response—but those don’t have recent legislative precedent for Congress to copy.

2025 Government Shutdown: Funding crisis driven by expiring enhanced ACA premium subsidies and routine appropriations deadlines. The precedent: 2019 government shutdown (Trump administration versus Democratic House over border wall funding). The analogous response: Refuse to negotiate while government is closed, frame as zero-sum political contest, wait for public pressure to force capitulation. The problem: The 2019 shutdown involved a single-issue dispute with a binary outcome (fund the wall or don’t). The 2025 shutdown involves the intersection of healthcare subsidy policy affecting millions, depleted SNAP contingency funds, cascading operational failures across multiple agencies, and the technical complexity of budget reconciliation procedures. This isn’t a standoff that ends when someone blinks—it’s a system failure requiring coordinated policy interventions across multiple domains.

The precedent trap leads both parties to treat this as political theater rather than policy crisis. Republicans cite 2019 to argue that Democrats will eventually cave to public pressure. Democrats cite 2019 to argue that Republicans will take the political blame. Both analogies miss the actual problem: the policy mechanisms are fundamentally different. You cannot negotiate your way out of expired statutory authorities. You cannot wait out depleted contingency funds. The 2019 playbook assumes the crisis is purely political; the 2025 reality is operational and technical. The government isn’t shut down because one side lacks political will—it’s shut down because the legislative architecture cannot process complexity fast enough to prevent cascading failures.

“The government isn’t shut down because one side lacks political will—it’s shut down because the legislative architecture cannot process complexity fast enough to prevent cascading failures.”

Meanwhile, 42 million Americans receive half their food assistance, not because anyone decided to cut SNAP by 50%, but because the contingency fund math doesn’t align with political negotiation timelines. Children lose Head Start access, not because anyone voted to defund early education, but because grant cycles don’t pause for shutdowns. Air traffic controllers call in sick, not because they’re making a political statement, but because they’re working without pay during the holidays. These aren’t political consequences—they’re system failures that occur when political processes cannot accommodate operational complexity.

The precedent trap is particularly dangerous for novel problems—challenges that genuinely don’t have historical analogs. Climate change operates on timescales and feedback loops unlike anything in political history. Artificial intelligence doesn’t map cleanly onto any existing regulatory framework. Pandemics caused by novel pathogens with unknown characteristics can’t be addressed with the last pandemic’s playbook.

Yet the political system demands precedent. Legislators need to cite past successes to justify present action. Voters need to hear that we’ve done this before. The media frames every story as “like when...” This makes reasoning by analogy feel safe, even when it’s catastrophically wrong.

The structural problem: Politicians are individually rational to use analogous reasoning (it provides political cover and simplifies communication), but the system-level result is that we systematically misdiagnose and mistreat novel problems. Each politician optimizes for their own survival; the collective outcome is intellectual regression.

Conclusion: The Anti-Intellectual Architecture

The American political system doesn’t fail to solve complex problems because we lack smart people or good intentions. It fails because the architecture itself is anti-intellectual—designed, through structural incentives, to punish the very sophistication that modern governance requires.

The soundbite imperative ensures that only communicable solutions survive, regardless of effectiveness. The expertise paradox rewards false certainty over genuine knowledge. The precedent trap applies old solutions to novel problems. Each incentive is individually rational for political survival; collectively, they create a system that cannot think.

This is not a problem we can solve by electing better politicians. Individual leaders, no matter how capable, operate within structural constraints. A politician who embraces nuance, acknowledges uncertainty, and proposes novel solutions will lose to one who offers simple answers, projects confidence, and cites precedent. The system selects for intellectual regression.

The consequence is visible in every major policy domain. We applied demand-side stimulus to a supply-side crisis and created inflation. We debate healthcare in soundbites while 180 million people depend on a system no one can explain in ten seconds. We reason by analogy about artificial intelligence—a technology with no historical precedent—because admitting novelty feels like admitting ignorance.

This is the second structural failure of American governance. In Legislative Servitude, we showed how the transparency paradox captures legislators, turning public servants into servants of special interests. Here, we’ve shown how the anti-intellectual architecture makes sophisticated policy impossible. Together, these design flaws explain why democratic governance appears broken: it’s not that the people are failing the system—the system is failing the people.

This is not a problem we can solve by electing better politicians. Individual leaders, no matter how capable, operate within structural constraints. A politician who embraces nuance, acknowledges uncertainty, and proposes novel solutions will lose to one who offers simple answers, projects confidence, and cites precedent. The system selects for intellectual regression.

The consequence is visible every day of this shutdown. As Day 36 becomes Day 37, then Day 38, the debate remains locked in soundbites while the operational reality becomes more dire. Politicians on both sides can explain, in ten seconds or less, why the other party is at fault. Neither can explain, in any amount of time, how to actually fix the intersection of healthcare subsidy policy, appropriations procedures, contingency fund mechanics, and operational continuity. The architectural failure is complete: the system that should solve complex problems cannot even process them.

We applied demand-side stimulus to a supply-side crisis and created inflation. We debate healthcare in soundbites while 180 million people depend on a system no one can explain in ten seconds. We shut down the government over healthcare subsidies while food assistance gets cut in half—not because anyone chose to cut it, but because the political timeline doesn’t match the operational timeline. We reason by analogy about novel problems because admitting novelty feels like admitting ignorance. Every major policy domain reveals the same failure: sophisticated problems compressed into simple narratives, with predictable disasters following.

This is the second structural failure of American governance. In Legislative Servitude, we showed how the transparency paradox captures legislators, turning public servants into servants of special interests. Here, we’ve shown how the anti-intellectual architecture makes sophisticated policy impossible. Together, these design flaws explain why democratic governance appears broken: it’s not that the people are failing the system—the system is failing the people. Right now. In real time. With measurable consequences for millions.

But design flaws can be redesigned. Systems can be re-engineered. In Part II, we’ll show how to build institutional architecture that rewards nuance instead of punishing it—creating the conditions where sophisticated analysis becomes politically rational rather than politically suicidal. We’ll examine how other domains (monetary policy, jury deliberation, scientific research) have solved this problem, and how those lessons apply to governance.

The question is not whether we need nuanced policy—the 42 million Americans receiving half their food assistance have already answered that question. The question is whether we can engineer systems that make nuance survivable for the politicians who attempt it, and whether we can do it before the next crisis makes Day 36 look like a warm-up.

We don’t need better politicians. We need better systems. And better systems require the intellectual courage to acknowledge that complex problems demand complex solutions—not because we prefer complexity, but because reality requires it. The shutdown will eventually end. The question is whether we’ll learn from it, or simply wait for the next precedent to misapply.

But understanding the anti-intellectual architecture raises a deeper question: Why does this system fail even when politicians try? In Part II, we examine the three catastrophic failure modes that emerge when this architecture confronts genuine complexity. In Part III, we’ll show how to build systems that reward nuance instead of punishing it.

Endnotes

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, Public Law 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (March 27, 2020).

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index data. As of September 2025, inflation was 3.0% on a twelve-month basis, above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target.

J.D. Power Specialty Valuation Services, “2021 Year-End Review” (February 2022). Travel trailer values averaged 39.1% higher in Q3 2021 compared to Q3 2020; for the full year 2021, travel trailers averaged 32.8% higher than 2020 and 42.5% higher than 2019.

S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller Home Price Index. Real house prices increased 15 percent from July 2020 to July 2021, and 20 percent from February 2020 to September 2021. See also “Why, and Where, are Housing Prices Rising?,” Econofact (February 2, 2022).

Erik P. Bucy and Maria Elizabeth Grabe, “Image Bite Politics: News and the Visual Framing of Elections,” Journal of Communication 57 (2007): 652-675. The average soundbite was 43 seconds in 1968, declining to approximately 8-10 seconds by the 2000s.

“U.S. Health Care Coverage and Spending,” Congressional Research Service, IF10830 (December 2023). As of 2023, an estimated 180 million individuals were covered by group coverage (largely employer-sponsored insurance).

Robert Warren, “US Undocumented Population Continued to Fall from 2016 to 2017,” Center for Migration Studies (2019). In 2017, an estimated 4.9 million, or 46 percent, of unauthorized immigrants had overstayed visas. See also Center for Migration Studies (2017) report estimating 42% of the undocumented population were overstays.

Amy Gershkoff and Shana Kushner, “Shaping Public Opinion: The 9/11-Iraq Connection in the Bush Administration’s Rhetoric,” Perspectives on Politics 3, no. 3 (September 2005): 525-537. See also Bruce Riedel, “9/11 and Iraq: The making of a tragedy,” Brookings Institution (March 9, 2022).

CNN Politics, “Government shutdown updates: Trump administration and election news” (November 4, 2025). The shutdown became the longest in U.S. history on its 36th day, surpassing the previous 35-day record set during Trump’s first term in 2019.

U.S. Department of Agriculture court filing, Massachusetts v. USDA (November 2025). The USDA indicated it would tap approximately $4.6 billion in SNAP contingency funds to provide 50% of normal benefits for November amid the shutdown. Approximately 42 million Americans receive SNAP benefits.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services notice (October 2025). More than 58,600 children in 134 Head Start centers across 41 states and Puerto Rico would not receive grants on November 1 if the shutdown continued.

Transportation Security Administration operational reports (October-November 2025). Airport staffing shortages led to delays at major airports including Boston, Burbank, Chicago, Denver, Houston, Las Vegas, Nashville, Newark, Orlando, Philadelphia, Phoenix, and Washington. On November 4, Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy indicated the DOT was considering closing sections of airspace due to staffing shortages.