Why You Can't Understand the Federal Budget (And Why That's About to Change)

P1.3: How We Can Finally See Where Our Money Goes

What If You Could Actually Understand the Federal Budget?

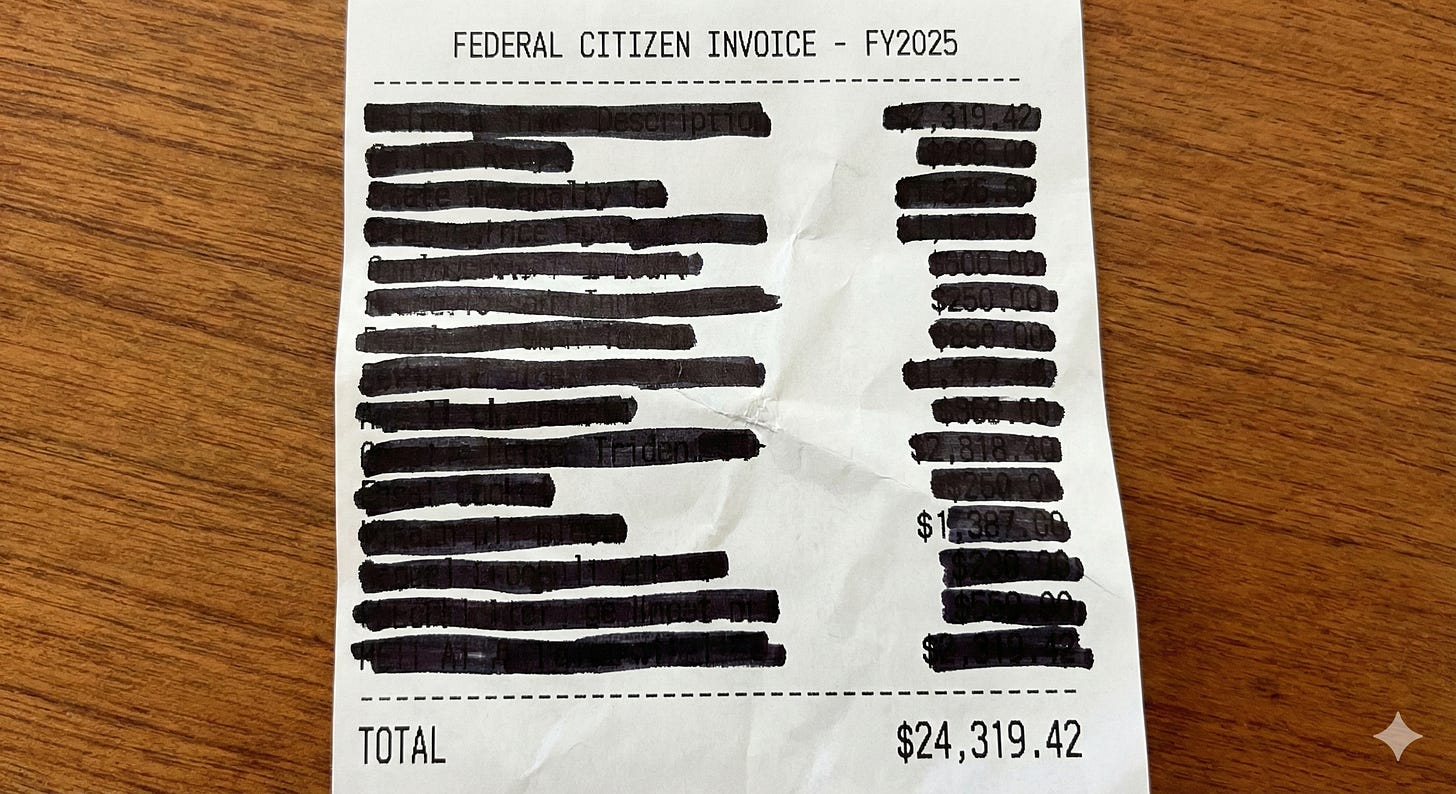

Not “understand it like an economist.” Not “understand it because you have a PhD in public policy.” Just... understand it. The way you understand your bank statement. The way you understand a restaurant menu.

What if someone asked “where do my tax dollars go?” and there was actually a clear answer?

This isn’t a fantasy. It’s a choice we haven’t made yet.

Every public company in America produces financial statements that any investor can read. Revenue. Expenses. What they spent money on. What results they got. Audited. Certified. Clear.

Every quarter, CEOs face shareholders and explain: “Here’s what we said we’d do. Here’s what we did. Here’s what it cost. Here’s what we got for it.” Investors ask hard questions. The CEO has to answer with real numbers.

Why don’t you get that?

You’re a forced investor in the federal government. You pay in through taxes. You can’t opt out. You can’t sell your shares if you don’t like the performance. You’re locked in for life.

And yet voluntary investors—people who can walk away anytime—get clearer financial information than you do.

That’s not inevitable. That’s a design choice. And design choices can be changed.

What Budget Transparency Actually Looks Like

Let me show you what’s possible. Not abstract theory—concrete examples that exist right now.

The Shareholder Meeting You Deserve

Imagine this: Once a year, separate from the State of the Union, the President presents the federal government’s financial performance directly to citizens.

Not theater. Not applause lines. Actual accountability.

“Here’s what we said we’d spend last year. Here’s what we actually spent. Here’s what programs were supposed to achieve. Here’s what they achieved. Here are the numbers, independently audited. Now—questions?”

Every public company CEO does this quarterly. They face real questions about real performance. If shareholders don’t like the answers, they can sell.

You can’t sell your citizenship. Shouldn’t you get at least as much accountability as someone who can walk away?

The Financial Statement That Should Exist

One document. Clear categories. Readable by a normal person.

All revenue sources (where the money comes from)

All spending categories (where it goes)

Assets and liabilities (what we own, what we owe)

Year-over-year comparison (is it getting better or worse?)

Independently audited (certified accurate by someone with no stake in the outcome)

Every public company produces this. Every state government produces some version of this. New Zealand produces this nationally and publishes it within months of their fiscal year ending.1

This isn’t revolutionary. It’s basic accounting. The federal government just... doesn’t do it.

The Dashboard That Could Exist Tomorrow

Searchable database. Updated continuously. Drill down from agency to program to contract to transaction.

“How much did we spend on veterans’ healthcare last year?” Clear answer. “What did that new infrastructure program actually build?” Clear answer. “How much went to contractors vs. direct spending?” Clear answer.

The technology exists. Private companies do this routinely. USAspending.gov was supposed to do this—but 92% of federal managers have never even heard of it, and the data is incomplete and inconsistent.23

The capability exists. The will doesn’t.

The Trade-Off Tool Citizens Deserve

Interactive platform. Real numbers. Real choices.

“If you increase defense spending by $50 billion, here’s what you’d have to cut—or here’s how much more you’d need to borrow.”

“If you want to balance the budget, here are the actual options: cut these programs, raise these taxes, or some combination.”

Cities like New York, Paris, and even Portugal at the national level have experimented with participatory budgeting—letting citizens directly allocate portions of public funds.4 It’s not perfect, but it proves the concept works.

The point isn’t that any one of these is THE solution. The point is: solutions exist. Other places do this. The technology exists. The knowledge exists. We just haven’t demanded it.

Why You Can’t Access This Yet

So if all this is possible, why don’t we have it?

Here’s where my wife comes in.

She asked me a simple question: “Can you explain the federal budget to me? Like, where does our money actually go? And what’s the deal with trade deficits?”

That last part is telling—trade deficits aren’t even part of the federal budget. They’re a completely different economic concept. But the terms sound similar, politicians blur them constantly, and even a financially literate attorney conflates them. That’s not her failure. That’s a communication system designed to confuse.

This is someone who runs her own business and creates financial statements from scratch. She’s an attorney who analyzes client finances professionally. She reads balance sheets the way most people read restaurant menus.

And yet—the federal budget remains incomprehensible to her.

If you’ve ever tried to understand the federal budget and given up, you probably blamed yourself. “I must not be smart enough.” “I should have paid more attention in economics class.” “It’s just too complicated for regular people.”

That’s wrong. The confusion isn’t your fault.

When a business owner who reads financial statements professionally can’t understand the federal budget, that’s not a personal failure. That’s a system designed to be incomprehensible.

The Design Failure

Think about the apps on your phone. How many required a training course before you could use them? Probably none.

In software design, there’s a fundamental principle: when users can’t figure out your interface, that’s not a user problem—that’s a design problem.

The federal budget is the worst-designed interface in America. And it’s not an accident.

Simple questions have no clear answers:

“How much do we spend on military?” Could be $800 billion (DoD budget) or $1.5 trillion (including VA, nuclear weapons in the Energy Department, intelligence agencies, debt interest from past wars).5 There’s no single agreed-upon number for one of the most basic budget questions.

“What’s the difference between the trade deficit and the budget deficit?” Politicians deliberately blur these terms. “We’re losing money to China” could mean many different things—and that ambiguity is useful for those who benefit from confusion.

“Should we balance the budget?” The debate gets compressed into “balance it!” vs. “debt doesn’t matter!” when the real question is when does debt make sense (like a mortgage—an investment that builds value) vs. when is it reckless (like borrowing for things that don’t pay off)?

These aren’t hard questions. They’re made hard by design.

Who Benefits from Your Confusion

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: the people who could fix this benefit from not fixing it.

Incumbents can’t be held accountable for things voters can’t understand.

Special interests can hide benefits in legislation nobody can parse.

Both parties can claim credit and dodge blame because nobody can trace cause and effect.

When budget surpluses appeared under Clinton, was it his policies or the dot-com boom? When deficits exploded under Bush, was it tax cuts or 9/11? The opacity makes these questions unanswerable—which is convenient for everyone in power.

Structurally, both parties benefit from this confusion. When nobody can trace cause and effect, incumbents of all stripes can claim credit, dodge blame, and keep the game going. In a word: they avoid accountability—which helps them get re-elected.

The Reforms That Keep Failing

We’ve actually tried to fix this. Repeatedly.

1990: The Chief Financial Officers Act aimed to bring private-sector accounting standards to government. Thirty-five years later, it’s still not fully implemented.6

2006: Congress created USAspending.gov to track federal spending. Result? Most federal managers don’t know it exists, the data has massive gaps, and it goes offline during government shutdowns.23

2014: The DATA Act aimed to improve data quality. GAO still finds major gaps, inconsistent standards, and undisclosed limitations.7

Each reform passed with bipartisan support. Each was quietly defeated through passive resistance, underfunding, and exploitation of complexity.

The system doesn’t just resist transparency—it actively defeats attempts to create it.

But here’s what that history actually proves: the problem is known, the solutions exist, and the only thing missing is sustained public demand.

What Opacity Actually Costs Us

Forget the trillions in waste. Forget the failed audits. Those numbers are important, but they’re not the real cost.

The real cost is learned helplessness.

People who see problems clearly but believe nothing can be done. People like me. People like you. People like your uncle you argued with at Thanksgiving dinner.

So how do they react? They default to tribal loyalty—”my team says it’s good”—because independent evaluation is impossible.

Even countries that try to do better struggle. New Zealand ranks near the top globally for budget transparency—unified financial statements, independent audits, citizens’ budget documents, the works.1 And yet, when researchers asked New Zealand citizens about their experience trying to engage with the budget process, one described it this way: “At the moment it’s like banging on a closed door. You have to push and yell your way in, and even then you don’t know what happened after you’ve made all the effort.”8

In other words: even in one of the world’s most transparent systems, citizens push and push for answers, and when they finally get a response, it still doesn’t tell them what they actually wanted to know.

If that’s what “good” looks like, imagine what our opacity produces.

The Accountability Gap We Can Close

Let’s make the contrast stark.

What business owners face:

Must pass audits or face consequences

Personal liability under Sarbanes-Oxley

SEC enforces standards

Investors can exit if unsatisfied

Clear financial statements required by law

What government provides:

Can fail audits indefinitely (DoD: 7 years running)

No personal liability for officials

GAO can only recommend

Citizens are trapped

Maze of contradictory documents

My wife—a business owner and attorney—must maintain clear financial records, face potential IRS audits, and could lose her license for serious violations.

The federal government, spending $6.8 trillion of citizens’ money, operates under looser standards than her small business.

If a CEO presented financials as opaque as the federal budget, they could face prosecution under Sarbanes-Oxley. Voluntary investors are protected by federal law. Forced investors—you and me—are not.

This gap isn’t inevitable. It’s a choice. And choices can be changed.

The Big Tent: Who This Unites

This isn’t left vs. right. It’s citizens vs. system.

Fiscal conservatives: Transparency is the ultimate tool to hunt waste. You can’t cut what you can’t see.

Progressives: The only way to prove social programs work is with evidence. Opacity is the enemy of evidence-based policy.

Libertarians: You want limited government? Start by making its current footprint visible and measurable.

Business people: You meet these standards every quarter. Why should government be exempt?

Populists (left and right): You believe insiders rig the game. You’re right. Opacity is the mechanism they use to do it.

Everyone who isn’t currently in power benefits from transparency. Everyone currently in power benefits from opacity.

That tells you everything about why we don’t have it—and everything about what it will take to get it.

One Voice, One Demand

You might be thinking: “This sounds good, but the system is too broken. Nothing ever changes. Why would this be different?”

Here’s why: because the demand is simple enough that everyone can unite around it.

We’re not asking you to become a budget expert. We’re not asking you to pick sides on complex policy debates. We’re not asking you to solve the deficit or fix entitlements or restructure government.

We’re not even asking you to define what budget transparency should look like. You don’t know. You shouldn’t have to know. But you’ll know it when you see it.

And if we really have a government for the people—a government that serves its citizens—then it should figure out how to meet that demand.

You can’t have government for the people if people can’t understand how their government spends their money. That’s not radical. That’s the founding promise.

We’re asking for one thing:

The first demand is simple enough to fit on a bumper sticker:

“We should be able to see where our money goes.”

That’s it. That’s the foundation.

Not as a favor. Not as a nice-to-have. As a fundamental requirement of democratic governance.

Once that’s non-negotiable—once citizens can actually see where money flows and what results it produces—everything else becomes possible. Debates about waste, priorities, trade-offs, and reforms finally have a foundation of shared facts.

The System Will Resist. That’s How You Know It’s Right.

Defense will claim national security. Agencies will claim implementation burdens. Special interests will mobilize. Both parties will find reasons why transparency threatens them.

When everyone in power opposes something, and everyone outside power wants it—that’s not a policy debate. That’s a system protection racket.

But here’s what the powerful forget: there are more of us than there are of them.

If you want change, you’re going to have to demand it. And me. And your neighbor down the street. And your uncle you argue with at Thanksgiving dinner. All of us—together.

That’s the big tent. Not built around left or right. Built around citizens vs. system.

We could have clarity. We’ve chosen opacity. That choice can be changed.

Not by electing better people into a system that hides the scoreboard. By changing the system itself. By building one voice that can’t be ignored.

Democracy requires informed consent. Right now, informed consent is structurally impossible.

That’s not a bug in the system. That’s the system working exactly as designed.

Time to design something better.

If this resonates with you, you’re not alone. The Statecraft Blueprint applies this same structural lens to every governance failure - from campaign finance to regulatory capture to why Congress can’t function. Not by picking winners in policy debates, but by designing systems where policy debates can actually lead somewhere.

We want a functional government. Share the symbol. Subscribe. Let’s build the demand they can’t ignore.

[Share on LinkedIn] | [Share on Facebook] | [Share on Bluesky] | [Share on X]

References

Footnotes

International Budget Partnership, “Open Budget Survey 2024.” New Zealand scored 87/100, tied with Georgia, just behind South Africa at 89/100. New Zealand previously held the #1 position from 2006-2019. New Zealand Treasury publishes audited government financial statements within months of fiscal year end. ↩ ↩2

GAO-20-75, “DATA Act: OMB, Treasury, and Agencies Need to Improve Completeness and Accuracy of Spending Data and Disclose Limitations” (November 2019), and GAO-22-104127. Survey found 92% of federal managers surveyed in 2020 were unaware of USAspending.gov. ↩ ↩2

GAO reports on USAspending.gov data quality (GAO-20-75 and subsequent reports, 2019-2024). Documentation shows large portions of award-level data elements are incomplete or inconsistent with source records, with only 24-34% of award transactions fully consistent. Reports also document missing billions in reported awards and site outages during government shutdowns. ↩ ↩2

New York City Civic Engagement Commission, “Participatory Budgeting in NYC” (ongoing since 2011). Paris implemented citywide participatory budgeting (”Budget Participatif”) in 2014 with annual cycles allowing residents to propose and vote on municipal investments. Portugal launched a national participatory budget in 2017, making it one of the first countries to implement participatory budgeting at the national level. ↩

Estimates of total national security spending that include Department of Defense base budget, Overseas Contingency Operations, Department of Energy nuclear weapons programs, Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Homeland Security, intelligence community, and interest on debt attributable to past military spending range from $1.0 trillion to $1.5 trillion annually. See: Smithberger, Mandy, “The Pentagon’s $1.4 Trillion National Security Budget,” Project on Government Oversight (2024); and Hartung, William D., “The Trillion Dollar National Security Budget,” Center for International Policy (2023). ↩

Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990, Public Law 101-576. Intended to bring private-sector accounting standards to federal agencies through mandated CFO positions and audited financial statements. Implementation remains incomplete 35 years after passage, particularly for consolidated department-wide statements. ↩

Digital Accountability and Transparency Act of 2014, Public Law 113-101. Intended to improve federal spending data quality and standardization. GAO reports document improvements in data availability while noting persistent issues with completeness, consistency, and disclosure of limitations. ↩

New Zealand Treasury, “Towards an Open Budget: Qualitative report to understand stakeholders’ views about making the budget more open and transparent” (2017). Stakeholder feedback on perceived barriers to meaningful public participation in the budget process despite transparency efforts. ↩

Your posts excite me in a way that few do. You trace the underlying dysfunction that is baked into the structure, non-partisan. Of course our government should have as much accountability as any small company on the stock market! Of course we should be able to understand our budget. I have no idea how to make this happen, but I want in.

We're currently having to think through how to redesign our government from the ground up, around anti-corruption, affordability, and protecting our most vulnerable. It would seem that budget accountability falls under anti-corruption... because of course there is wild corruption built into an opaque system.