What Is Education Even For?

P4.2.2: You can't design a system without agreeing on the goal

A couple weeks ago I told you about being labeled stupid. About a system that only works for one type of mind, losing bright students who think differently.

But that’s just one failure mode. Before we talk about how to redesign education, we need to answer a more fundamental question:

What is education even for? What public purposes should it serve?

This matters because you can’t design architecture without first establishing the goal. Different goals produce different designs. And right now? We’re trying to serve every possible purpose simultaneously with no coherent architecture. That’s guaranteed failure.

So let’s start with first principles: Why have public education at all?

Why Public Education Exists

Before we can design an education system, we need to decide: What should it accomplish?

This should be democratically decided. Different societies make different choices based on their values and needs. All legitimate.

Education provides many potential benefits:

Economic competitiveness

Self-governance capability

Social integration

Family economic support

Human flourishing and personal development

Creativity and innovation

Social mobility

Character development

Some of these are measurable public goods—things that benefit everyone, not just the educated. Even if you personally never use calculus, you benefit from living in a society where someone does. Engineers design safe bridges. Doctors understand medical research. Economists model complex systems. Your life is better because other people have specialized knowledge, even if you don’t share that knowledge.

Some benefits are valuable but contested and hard to define. Different people genuinely disagree about what “human flourishing” or “good character” means.

For this exercise, I’m focusing on four that I believe qualify as clear public purposes. You might choose differently. That’s fine—that’s the conversation we should be having. Not “how do we better deliver what we inherited?” but “what outcomes do we actually want?”

These aren’t aspirational goals. They’re constraints imposed by the kind of society we’re trying to run.

Try removing any one of these and see what happens:

Remove economic competitiveness → stagnation and decline

Remove self-governance capability → democracy collapses

Remove social integration → fragmentation and instability

Remove family economic support → the workforce itself becomes unsustainable

These are load-bearing. Here are the four I’d focus on:

Economic Competitiveness

An educated workforce isn’t just good for individuals. It’s necessary for nations to compete globally. Countries without universal education can’t develop modern economies. When a population can’t participate productively in the economy, everyone’s prosperity suffers—not just the uneducated.

This is observable fact. Look at countries that lack broad educational access. They can’t compete in knowledge economies. They can’t attract investment. They can’t build the infrastructure modern life requires.

Self-Governance Capability

Democracy literally doesn’t function without informed citizens who can evaluate arguments, understand how systems work, and participate meaningfully in civic life.

This isn’t partisan. It’s mechanical. A democratic system requires educated participants. If citizens can’t distinguish fact from propaganda, can’t evaluate policy claims, don’t understand how government actually functions—the system breaks down regardless of which party is in power.

You can see this happening now. Not because people are stupid, but because we’ve never systematically taught civic literacy.

Education helps. But government also needs to meet people where they are—we’ve written about this extensively in “Democracy Shouldn’t Require Heroic Effort“ and our work on budget opacity and government UI/UX. Both things need to improve: civic education AND government accessibility.

Social Integration

This one’s harder to talk about right now, but it’s important.

The United States has had birth rates below replacement level for years. An aging population with a shrinking workforce creates serious economic challenges—fewer workers supporting more retirees, difficulty sustaining economic growth, labor shortages in critical sectors.

Immigration is one of the primary ways countries address this demographic challenge. It’s not about values or culture—it’s about economic reality. You can have strong opinions about immigration policy, but the math is the math: We need workers.

And IF we’re going to have immigration (which economically, we need), THEN we need systems to integrate newcomers into society. Not assimilation that erases identity, but integration that creates shared foundation—language, civic knowledge, ability to participate in society and economy.

Without this, you get parallel societies that can’t cooperate effectively. That’s economically destructive and socially unstable. Every successful diverse society has figured this out. America historically did this well through public education. We’re forgetting how.

This isn’t about whether you personally like immigration or want more of it. This is about acknowledging that IF it’s happening (and economically it needs to), THEN we need functional integration mechanisms. Education is how societies build the shared foundation that lets diverse populations function together productively.

Family Economic Support (Let’s Be Honest)

Here’s the uncomfortable truth we don’t want to acknowledge: In modern economy, two-income households are necessity, not choice.

This wasn’t always true. In the 1960s, single-income families were the norm. School schedules—3pm dismissal, summers off—assumed a parent at home.

Go back even further: Those schedules were designed for agricultural economy. Summer break for harvest season. Early dismissal for farm chores. We’ve been carrying forward design decisions from the 1800s.

The key insight: Wages kept pace with general inflation, but the cost structure of adult life didn’t.

Current economic reality:

70% of mothers with children under 18 are in the workforce

Median home price requires two incomes in most markets

Real wages have been essentially stagnant since the 1970s—but what does that actually mean? In 1970, median household income was about $10,000. Adjusted for inflation, that’s roughly $78,000 in today’s dollars. Median household income today is around $75,000. So wages kept pace with general inflation.

But here’s the problem: In 1970, the average house cost $25,000—about 2.5 times the average annual salary. Today, with salaries around $75,000, the median home costs $430,000—about 5.75 times the average annual salary. In expensive markets, this imbalance is much worse. Housing got 121% more expensive than inflation alone would predict.

Other essentials exploded similarly: Healthcare costs 7x more than inflation predicts. College tuition 8.5x more. Childcare costs have outpaced inflation significantly.

Meanwhile, some goods got cheaper (electronics, consumer products). But the big-ticket items that determine financial stability—housing, healthcare, education, childcare—all became dramatically less affordable.

Single-income families are increasingly rare and economically stressed

Some people advocate returning to traditional single-income families. That’s a legitimate personal choice. But you can’t design public systems around one group’s ideal when economic reality makes it impossible for most families.

If working parents can’t safely leave children during work hours, family economic stability collapses. This has ripple effects across the entire economy.

So let’s be honest: Education increasingly functions as childcare. We’re afraid to admit it because it sounds like we’re not prioritizing learning, like we’re warehousing kids, like we’re treating teachers as babysitters.

But this dishonesty creates terrible design:

Schools run 9am-3pm at the elementary level when most jobs run 8am-6pm

Three months of summer break when parents work year-round

No provision for sick children when parents can’t miss work

Teachers expected to educate AND supervise, doing neither optimally

During WWII, when we needed women in the workforce, we built extensive federal childcare infrastructure through the Lanham Act. Then we dismantled it after the war. The need never went away—we just stopped acknowledging it.

What if we acknowledged childcare as a legitimate public purpose and designed for it explicitly?

This isn’t about lowering standards or treating kids as inconveniences. It’s about designing systems for the world we actually live in, not the world we wish existed.

What These Purposes Require

So we’ve established four public purposes (at least, the four I’d prioritize—you might choose differently):

Economic competitiveness

Self-governance capability

Social integration

Family economic support

The question becomes: Given these purposes, what do people actually need to know?

What follows is my personal framework. You’ll disagree with some of it—that’s fine. Maybe you think statistical literacy is essential and I’m wrong to call it “highly valuable.” Maybe you think civic literacy feels like indoctrination (I’ll address that). Maybe you have different priorities entirely.

The real point isn’t that MY list is perfect. It’s that to show you how to design a functional education system, I need SOME goals to work toward. Your goals might differ—that’s a legitimate debate worth having. But I’m trying to illustrate the method: how governance architecture thinking approaches complex system design. We start with clear purposes, then design architecture to achieve them. All of this would look different with different goals, but the process would be the same.

Think of what follows as capability tiers, not graduation requirements. Each tier increases the quality of participation and capability, not the moral worth of the person. A system can treat something as essential without requiring universal mastery—by making it accessible, reinforced, and reachable at multiple points in life.

Here’s how I would break it down:

The Foundation (Can’t Do Anything Else Without These)

These are the building blocks. Without them, nothing else works:

Literacy - Read and write proficiently, understand complex texts, communicate clearly in writing. This hasn’t changed since the 1800s and won’t change. You cannot participate in modern society without this.

Arithmetic - Basic mathematics, quantitative reasoning, understand how numbers work in context. Again, foundational. Hasn’t changed, won’t change.

Learning How to Learn - Acquire new skills throughout life. Navigate changing technology. Transfer knowledge across domains. Recognize when you need expertise and how to find it.

Why this is foundational: Knowledge itself is accelerating. The average person changes careers 5-7 times. Technology changes constantly. Even staying in the same career requires continuous learning as the field evolves. This might be the most important competency because it enables acquiring all the others as they evolve.

But here’s what we actually teach: I told you about my calculus teacher who said he could give me better grades if I just did the homework, even though I aced the tests. I barely passed instead. The system prioritized compliance over mastery. That’s the opposite of learning how to learn. We teach students to follow prescribed paths and not deviate—exactly the wrong skill for a world that requires constant adaptation.

Mental and Emotional Health Literacy - Recognize signs of anxiety and depression in yourself and others. Understand when to seek help. Basic emotional regulation skills. Healthy versus unhealthy coping mechanisms. How to support others who are struggling.

Why this is foundational: You can’t learn anything else if you’re drowning mentally. The mental health crisis in young people is catastrophic. We have the knowledge to teach these skills early. Some schools are doing this, though often ad hoc rather than systematic curriculum. We need to make it foundational.

One critical component most people miss: Music isn’t optional enrichment—it’s essential infrastructure for emotional regulation, especially in children. As Dr. Bruce Perry documents in “What Happened to You?,” music plays a vital role in helping kids process emotions and develop self-regulation skills. Yet we treat it as disposable “arts” funding, not the foundational tool it actually is.

Essential for Modern Life (Can’t Function Without These)

These build on the foundation. You need them to navigate the modern world:

Digital Literacy - Navigate internet and digital tools. Understand how algorithms shape information feeds. Recognize scams, phishing, digital manipulation. Basic troubleshooting. Protect personal information and privacy.

Why essential: You literally cannot participate in the modern economy without this. Job applications, banking, healthcare, government services—all require digital competence.

Information Literacy - Evaluate source credibility. Distinguish fact from opinion. Recognize manipulation techniques and propaganda. Understand bias and framing. Cross-reference claims. Identify AI-generated content versus human-created.

Why essential: We live in information abundance with wildly varying quality. You need to be able to tell the difference between news and propaganda, expertise and grift, or you’re just believing whoever sounds most convincing.

Critical Thinking - Evaluate arguments, spot logical fallacies, reason through problems. Separate good arguments from bad ones regardless of whether you like the conclusion.

Why essential: This used to be implicit in education. It’s not anymore. People need explicit training in how to think through complex problems and evaluate competing claims.

Financial Literacy - Understand interest, debt, and credit. Read contracts and identify predatory terms. Basic budgeting and long-term planning. How taxes work. Retirement savings basics. Economic concepts that affect daily life.

Why essential: Economic competitiveness requires citizens who can manage personal finances and aren’t constantly exploited by predatory lending, hidden fees, and financial products they don’t understand. Individual financial failures ripple through the economy.

Highly Valuable (Makes You Much More Capable)

These make you a more effective citizen and participant in modern society:

Civic Literacy - How government actually works—not just “three branches” but how to access government services, how to participate beyond voting, how policy becomes reality, what different levels of government control, how to evaluate candidate claims.

Why valuable: You can’t participate effectively in self-governance if you don’t understand what you’re participating in. Note: This is about HOW the system works, not WHAT to believe. Teaching the structure of Congress isn’t indoctrination. Teaching which party you should vote for would be.

Statistical and Data Literacy - Understand graphs, percentages, probability. Recognize when statistics are being manipulated. “Correlation isn’t causation.” Sample size and significance. What numbers actually mean in context.

Why valuable: Modern policy debates are full of statistical claims. This helps you evaluate them instead of just believing whoever sounds most convincing. But you can function without it—take, for instance, an attorney who needs basic arithmetic day-to-day but doesn’t need trigonometry or calculus for their work.

Health Literacy - Understand how vaccines work and why they matter. Recognize medical misinformation. Understand how diseases spread in an interconnected world. Basic public health concepts. When to trust medical expertise versus when to question.

Why valuable but potentially contested: We’ve had multiple pandemics in twenty years, with more coming. Individual health decisions have public health consequences. But I acknowledge this can feel like indoctrination depending on your views about medicine. The question is: can we agree on teaching basic biology and germ theory even if we disagree about specific interventions?

AI Literacy - Understand what AI can and can’t do. Use AI as cognitive augmentation, not replacement. Recognize AI-generated content. Understand limitations and biases. Practical skills in working with AI tools. Critical thinking about AI outputs—verify, don’t blindly trust.

Why valuable: AI isn’t going away. The question is whether people learn to use it productively or get displaced by it. AI presents unique challenges—it can do cognitive work itself, creating risks of mental atrophy similar to how GPS eliminated navigation abilities. There’s so much to say about AI and education (including AI’s potential for personalized teaching) that it probably deserves its own essay. If you’d like to see me dig into that, let me know.

This is a lot—and we haven’t even started career-specific training or covered science and history in depth, or geography, literature, and other traditional subjects. Though note: Many of these weave together. Civic literacy naturally includes historical context (why our system is designed this way). Health literacy includes biological science. Statistical literacy connects to scientific method.

And here’s something important: You can be a fairly functional member of society without knowing where Georgia is on a map (the state or the country), or the difference between voltage, amps, and watts. I’m quite sure a sizable portion of the US population couldn’t find Georgia (either one) on a map, but they can manage to charge their phone everyday. They’re still productive members of society.

But if you don’t understand basic economics—that tariffs aren’t taxes on other countries, for instance—and you vote for someone who tells you they are, that has a material impact on your life. That’s why basic economics belongs in financial literacy. The economic consequences of policy decisions affect everyone, and citizens need to understand what they’re voting for.

Once you agree on the purposes, the rest of the design questions stop being philosophical. They become engineering.

The Brutal Assessment

I’m not arguing these things have zero value—I’m arguing that when time is finite, prioritization is design.

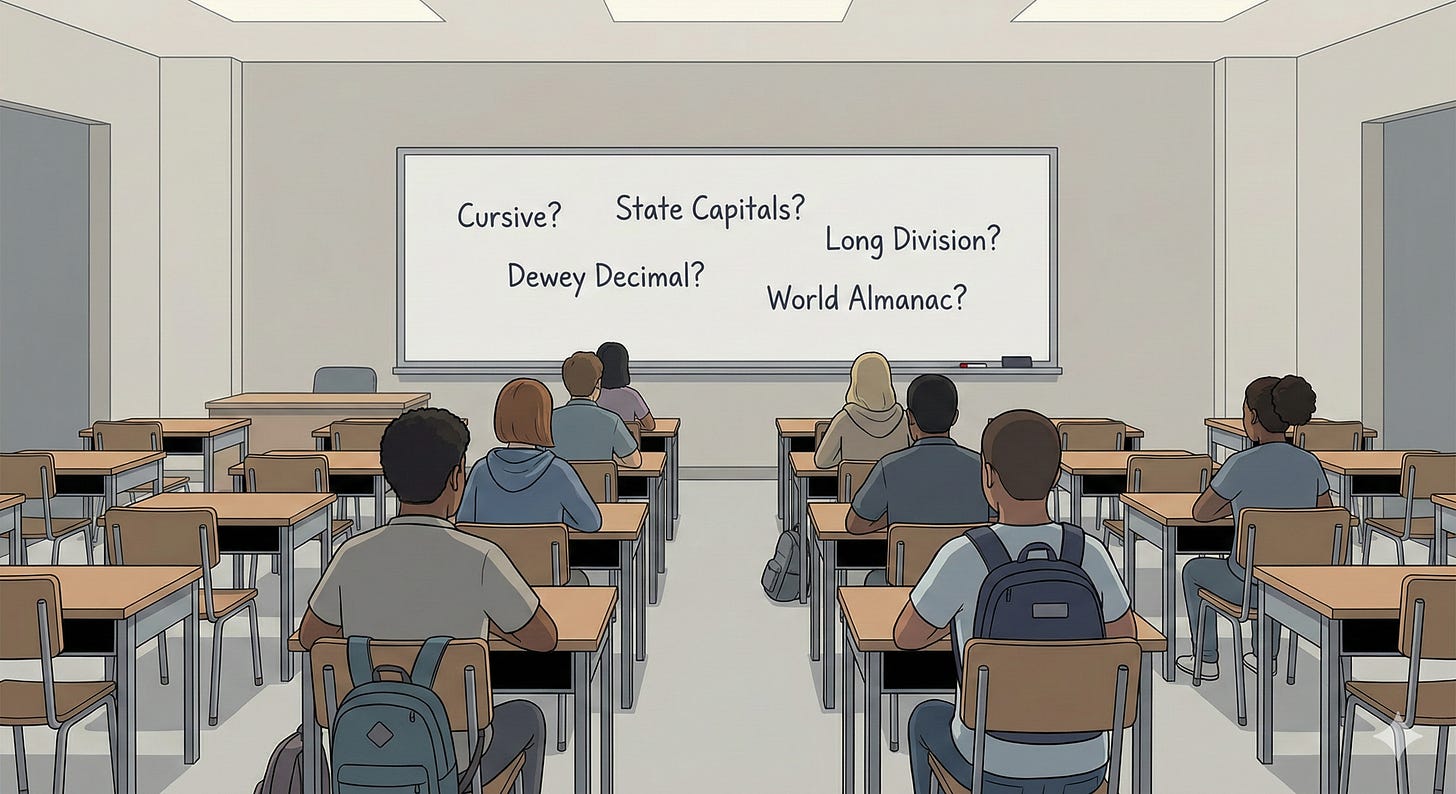

Meanwhile, we’re still teaching:

State capitals (Google exists, we all have phones, when was the last time you needed to recall that Tallahassee is Florida’s capital?)

Dewey Decimal System (completely obsolete with digital search)

Long division by hand (Remember 90s teachers saying “you won’t always have a calculator in your pocket”? Well, we do. We all carry them.)

Cursive (typing and voice input are increasingly replacing handwriting)

Here’s the pattern: We keep teaching things because “we’ve always taught them,” even when they’ve become functionally obsolete. Meanwhile, critical modern competencies go untaught because they weren’t in the traditional curriculum.

This is path dependency in miniature. We inherited a system, added layers without redesigning the foundation, and now we’re stuck teaching for a world that no longer exists.

The Stakes

Last week I showed you how the system fails students who think differently—bright minds lost because we only accommodate one cognitive style.

But look at what we just established. We’re not just failing neurodivergent students. We’re failing all students by not teaching the competencies that modern life requires.

Economic competitiveness? We’re sending workers into 2026 with 1950s skills, wondering why they struggle in modern economy.

Self-governance capability? We’re watching democracy strain under citizens who don’t understand how it works, who can’t evaluate information, who’ve never been taught civic literacy.

Social integration? We’re losing the shared foundation that lets diverse populations function together.

Family economic support? We’re forcing working parents to cobble together expensive aftercare and summer camps because we won’t acknowledge that childcare is a core function.

Not because people are stupid. Because we’re not teaching what they need to know.

We’re teaching state capitals and Dewey Decimal while not teaching statistical literacy. We’re requiring memorization of dates while not teaching information literacy. We’re dismissing at 3pm while parents work until 6pm.

This isn’t inevitable. But it’s also not just a simple choice we keep making.

People HAVE been questioning education for decades. If the response to my first essay is any indication, frustration with the system is widespread and long-standing. Reform attempts happen constantly. They fail spectacularly.

That’s not accident. It’s not incompetence. It’s structural—which is what we’ll explore in coming essays. Why is change so hard? What makes education reform different from just “demand more from our senators”? What governance architecture would actually enable the kind of transformation we need?

For now, the point is: We inherited a system designed for a world that no longer exists. We keep teaching obsolete skills while modern competencies go untaught. We pretend single-purpose (education) when we’re serving multiple purposes (education + childcare). We have no coherent framework for what we’re trying to achieve.

That can change. But first, we need to see what intentional design would actually look like.

Next Essay: What I Would Build

So we’ve established what someone actually needs to know to function in 2026. A foundation of literacy, arithmetic, learning to learn, and mental health. Essential competencies for navigating modern life. Highly valuable skills for engaged citizenship.

The question becomes: What would an education system designed to deliver these competencies actually look like?

Not “what system did we inherit?” but “what would we intentionally build?”

That’s what I’m going to show you next. Because this is a design problem. And design problems have design solutions.

We can do better than what we inherited. We can build education architecture that actually serves modern needs—that accommodates different ways of thinking, that teaches essential competencies, that prepares people for the world they’ll actually live in.

I’ll show you exactly what that looks like.

Aside from how to teach, there is also the why to teach. If what you are saying accurately reflects what is needed today, I think that's kind of depressing. I'm not saying you're wrong, but it sounds a bit dreary.

Things I wish I had learned in school include arithmetic, which I still can't do and don't understand, and civics, which I continue to learn but still don't know enough about to make a functional difference, and history, which I definitely was never taught beyond the false narratives they wanted to brainwash us with. I'm more invested in local survival and creating spaces we want to live in than I am in global competition.

The entire realm of the arts is as important as music. Visual communication, gardening, cooking, canning, making clothing, building a house, woodworking, electrical wiring, plumbing, survival training, first-aid, basic self-care, safety training, writing (cursive is not a waste of time, but good for developing hand skills), printing, acting, pottery, dance, fixing a car, playing a musical instrument, building a machine, purifying water, taking care of a cistern, & any other non-academic skills we need for self-sufficiency (formerly termed "vo-tech skills"). We should know how to survive in the event we cannot hop online and have what we need delivered to our homes. In addition to loss of self-sufficiency, losing these skills disconnects us from human history and inherited culture.

Absolutely agree.